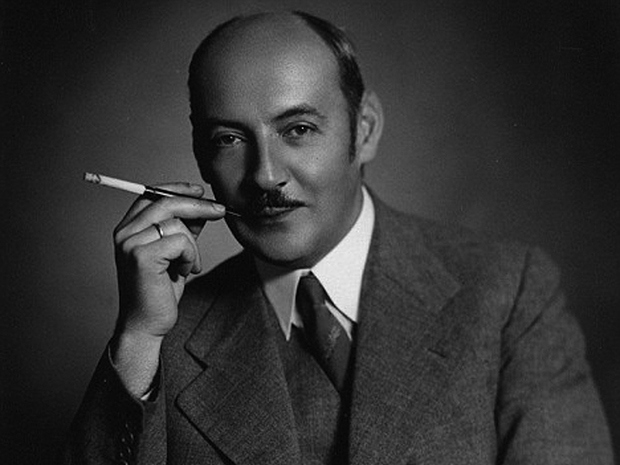

Albert Goering biography

When looking at WWII there are few names shrouded in more infamy than Goering. As Reichsmarschall, Hermann Goering was the highest rank in the Wehrmacht and one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany, answering only to Hitler himself. His position and role in the war means that the blame for many of the Nazi atrocities can be placed on his shoulders. He founded the Gestapo and was one of the chief architects of the holocaust – it was Goering who issued and implemented all of the practical details regarding the solution to the “Jewish Question”. However, to hundreds of Jews and political dissidents ‘Goering’ was also the name of their liberator and rescuer. During the Second World War, Hermann’s younger brother Albert risked both, imprisonment, and his own life to save hundreds more using his unique family connection.

Albert Goering facts

The Goering’s had a privileged upbringing. Their father Heinrich was Germany’s consul to German South-West Africa (Namibia today) and later Haiti. As a result, he was away for much of their childhood. Suspicion and rumour ran rife regarding their mother, Fanny, who was said to be having an extra-marital affair with a distinguished physician named Dr Hermann von Epenstein. It was von Epenstein who was at Fanny’s side as she gave birth to Hermann and when the youngest sibling Albert was born he announced that he would become Godfather to all 5 of the Goering children. The family’s main residences were Burg Veldenstein and Burg Mauterndorf, the former an imposing medieval stronghold in Franconia and the latter a castle that looks like it comes straight from the pages of a children’s fairy tale book.

When von Epenstein was a guest, he made sure he had the best room in the house – which was always said to be a short dash from Fanny’s bedroom. There is strong speculation that Albert was Fanny’s illegitimate son to von Epenstein. It was Albert who always got the most attention and affection from their godfather and the two bore an uncanny resemblance. Albert had his brown eyes and central European physical traits, whereas Hermann inherited the mothers classic Aryan looks of blonde hair and blue eyes.This theory is backed up by Albert’s only daughter Elizabeth. Long after Albert’s death she revealed that he confided in his ex-wife (Elizabeth’s mother) that he was the son of von Epenstein. If this conspiracy is true, it means that Albert – brother of one of the Holocaust’s most significant architects – was half Jewish.

Albert and Hermann Goering

The relationship between the two brothers was undeniably close when they were growing up and this remained true right up until Hermann’s death. Despite their close relationship, however, Albert and Hermann couldn’t be further apart when it came to their personalities and behaviour. Hermann was a problem child and struggled to stay in any of his boarding schools for a prolonged period. He preferred being outside and hated being cooped up in the classroom which caused him to act out. For example, before being expelled from his last school he cut the all of the school band’s cello and violin strings. His bad behaviour meant that he was sent to military school where he could channel his aggressiveness and hyperactivity. He forged a successful military career and became an ace fighter pilot, picking up many accolades in WWI. After the war, he became a disenfranchised exserviceman and prominent in the Munich beer hall which became a breeding ground for hate towards the Weimar government. This is where he met the failed artist Adolf Hitler who was just starting to make the slightest ripples in the political scene. Hitler’s passionate rhetoric resonated with Hermann and the two would become close allies for the rest of their lives.

Albert on the other hand was bookish and said to have a sad demeanor. He also served in WW1 as a communications engineer and in 1919 he went to the Technical University of Munich to study Mechanical Engineering. It was in the latter half of the 1920s that the relationship became somewhat frayed between the brothers.

Albert Goering quotes

Albert grew increasingly concerned over his older brother’s political activity, eventually shunning him and telling a close friend: “Oh, I have a brother in Germany who is getting involved with that bastard Hitler and he is going to come to a bad end if he continues that way”. Nevertheless, they were both able to put their differences aside and maintain a loyal and friendly relationship.

As the Nazis rose to power so did their use of violence and brutality towards those that did not submit to or fit their ideology. Sensing trouble, Albert left Germany and moved to Austria where he hoped to lead a quiet life as a filmmaker but there proved to be no escape from the tumultuous world that his brother was spearheading and after the Nazis successfully carried out the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria), Albert would have to move again. He became the Director of Exports for Skoda in Czechoslovakia which was appropriated by the Nazis to make military vehicles, planes, various components for weapons and cartridges. In the workplace, he turned a blind eye and even encouraged passive resistance to the Nazis. His staff were allowed to carry out their work slowly, purposefully miss deadlines and ‘forget’ to carry out tasks. Some of the best recollections and anecdotes from this period come from Karel Sobota, Albert’s personal assistant at Skoda. After the war, Sobota recalled with admiration how Albert remained unphased when the Nazis came to the factory and never relented on his personal beliefs and morals. Albert would never return the Nazi salute – both in and out of the factory – something which usually carried a hefty prison sentence if you were lucky and execution if you were not. One story purports that whilst in Bucharest, two Nazi officers saw Albert and recognised him as the Reichsmarschall’s brother and dutifully raised their arm and called “Heil Hitler” as was to be expected. Albert, straight-faced, replied “you can kiss my ass”.

Sobota tells of another humorous story that took place back in Czechoslovakia at the factory. One of Albert’s conditions was that every visitor, Nazi or not, be announced to him before entering his office. One SS officer disregarded this rule and marched into his office unannounced despite Sobota’s best efforts to block him. Outraged, Albert told the officer to wait outside of his door like a naughty schoolboy being reprimanded by the head teacher. Albert then called Sobota into his office, told him to sit down and they proceeded to talk about topics such as the weather. They even broke out some of Albert’s photo albums and took a trip down memory lane. Eventually Albert summoned the SS officer into his office calling him a “Nachtwatcher”.

Albert also used his family ties to rescue Jews and Czech resistance fighters. In the Autumn of 1943 Albert signed the travel papers and passports for a Jewish family he had befriended with his own hand and in a separate incident, when elderly Jewish women were told to scrub the pavement, he took off his coat and got down on his hands and knees to help them. The Nazi officer in charge was so mortified that he had made a public display out of a Goering that he sent everyone there home. He was known to say to Hermann “This is a good Jew Hermann even you can see that, I bet you could save him if you wanted” and sure enough much of the time Hermann did. Albert even managed to once persuade SS chief Heydrich to release a group of Czech resistance fighters that were being incarcerated by the Gestapo.

That’s not to say, of course, that Albert never got in trouble. He was arrested on numerous occasions but time and time again Hermann got him off the hook muttering “I swear this really is the last time Albert, I won’t be able to do this again”. Richard Sonnenfeldt, chief interpreter of the American prosecution team at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial, recalls in his book Witness to Nuremberg, how Hermann always felt he needed to prove himself to his younger brother: “We found a hundred people on Albert’s list that were freed. All because Goering had such a need to show off to his younger brother”.

Despite his courage and numerous acts of kindness, Albert still stood as a suspect in the Nuremberg trials due to his surname. He stunned interrogators when he produced a list of 34 people that he claimed to have rescued during the war. Originally the prosecutors dismissed this as another guilty Nazi clutching at straws in a bid to avoid the hangman’s noose. However, when notable people on the list started coming forward and vouching for Albert, the interrogators had to take notice. Kurt Pilzer, who with his family had escaped to the United States, was one on those names on the list and wrote to the Nuremberg prosecutors to plead Albert’s case. The prosecutors were dealt another bizarre twist when a new American interrogator arrived at the trials called Victor Parker. Parker told how his aunt, Sophie Paschkis, had married the famous composer Franz Lehár who happened to be number 15 on Albert’s list. Paschkis vouched for Albert, informing the interrogators that he was responsible for saving many Jews from going to concentration camps.

This wouldn’t be the end of Albert’s trials though. Following the war he was also wanted in Prague for Nazi collaboration. This time it was his faithful employees and Czech resistance fighters in the Skoda factory that came to his rescue. They felt they owed Albert a great debt for his role in the war because he kept themselves and the necessary authorities well informed by frequently divulging useful information and undermining the Nazis.

It wasn’t until 1947, after being locked up for 2 years, that Albert was truly free.

Hermann was the most high-ranking and important Nazi that the Allies captured alive and he was seen as something of a trophy as a result. His fate is well-known. He committed suicide by smuggling and swallowing a cyanide capsule in his cell the night before he was supposed to be executed for his war crimes.

The name Goering proved impossible to shake for Albert following the war but he refused to take the easy route and change it. In the immediate years he got by on an allowance supplied by von Epenstein. This didn’t last and he wound up being depressed, alcoholic and an adulterer which cost him his marriage and family who moved to Peru. Far from his aristocratic upbringing, he died a penniless drunk shunned from society because of his brother. True to his heraldic form, he married his housekeeper the week before he died so she could inherit his pension.

With deflated egos, heartbreak and poverty after WWII, the German people were ready to blame it on somebody – and Hitler found the group they could despise! Desperate people are dangerous.

LikeLike

My wish is that one day he receives the recognition he deserves even though he won’t be alive to see it. A last name in common with an infamous brother shouldn’t stand in the way of a good man’s reward.

LikeLike

does anybody know as to where I can find the Albert list of 34 names on the internet?

LikeLike